What Kind of 'Civilized' Are We Looking For?

The rhythms of Senegal continue to inform my life, well after my return

I have been back from Senegal for three weeks already, and yet still in many ways I am stuck there, still thinking about my time, sorting and processing it piece by piece. Maybe more than any other trip, going to West Africa has made me question the way I live here in the U.S., in New York, has made me question our values and what we deem necessary, how we interact with one another here versus there, the rhythms we have grown to accept as normal. It is, I know, the reason I went, to try to get out of the bubble I live in, out my fairly myopic vision of the world. On return, neighbors have looked at me wide-eyed, amazed that I went off by myself to this place they know nothing about.

“Is it…civilized?” someone asked. And I guess it depends on one’s definition of a ‘civilization,’ whether one is focused more on social kindnesses and manners, or more on the technological developments of a society. I went to hotels that kept handwritten ledgers and didn’t accept credit cards, and yet every passerby says “Bonjour, c’est va?” (Hello, how are you), strangers on the street offered me a spoon to share their food with them, and people who lived in very not-fancy circumstances still invited me in to their homes. I encountered far more ‘civil’ behavior in many ways than what I see here amidst highly-productive technologically savvy people, who race about getting ‘important things’ done, can barely take time to utter hello even when they know you, and boast about recycling while using a great abundance of disposable paper products that, when scarce during the pandemic, made our ‘society’ fly into a panic. We have a lot to learn from the people of Senegal, I just hope there is time before they “progress” to acting as uncivil as we often do.

Feb. 25th - Ziguinchor/Kafountine

I am sad packing up my things at Hotel Le Perroquet. It is such a beautiful spot in the world. My friend Abdou joins me for breakfast, and sitting out on the little beach by the river, I feel so at home. We hear a musician playing over the wall and we go to listen and greet him. He is playing the beautiful instrument Alpha sold me in Dakar (Gongoma? Bongoma? I cannot for the life of me figure, I’ve heard it called so many things…) I so appreciate now hearing someone play this beautiful yet simple instrument. I know exactly how the broken-off saw blades get affixed under a hand-carved wood bridge to the calabash, having seen it done before my eyes. I am amazed at how much I’ve been able to learn about this part of the world and its musical offerings in such a short time. I feel blessed and happy, and offer the gentleman a tip for his serenade.

Behind the reception desk, when I pay my bill added up from a hand-written ledger, I admire some thin wooden sculptures of women, similar to ones I’ve admired on the bar at Shrine, in Harlem. I ask Abdou if he thinks they might have some at the market I’ve heard about, that I’d wanted to visit the day before but felt unwell, and he says yes. He has friends there who make things like that (of course.) Even though we have only a short time before my driver is coming to take me to Kafountine, Abdou and I look at each other and decide to go for it. We jump up, laughing and head out to the curb just outside the hotel where he easily hails a taxi. We are both proud of our mutual spontaneity, and I am thrilled to have only a short time to shop, as I know how much I love all the things here…

At the little marketplace, I quickly peruse the jewelry for a puka shell necklace I want. The one I bought on Goree Island has disintegrated somehow. The sea air is hard on things. I see a beautiful djembe and want so badly to be able to buy it. Maybe next time I will think to arrange a way to ship things. But for now, I look at smaller things. I find a plain unvarnished wood sculpture like what I am looking for, and a kalimba. The shopkeeper, Souleymans Sadio L’ Americain (really!) is both a sculptor and a percussionist, like so many people in Senegal. He plays a little balafone while I play a kalimba, so fun!

We make a hasty retreat, Abdou laughing as he finds us a taxi at how I whisked through the market. He imitates me, turning this way and that, “How much, how much, how much?” He laughs. Sadly, we have to head back to the hotel with only a few minutes to spare before my driver arrives. I took a video of the drive, amazed by all the colors of textiles and walls as we passed through the town in a blur.

I have been forewarned by Kath at the Kora Workshop I am headed to that the driver, Hassan, might be late because the road between Kafountine and Ziguinchor he has to travel to get me and bring me back is rough.

He is in fact late but so friendly and apologetic, and anyway I wasn’t anxious to leave this ideal setting...I would have ordered a last Plate du Jour except the kitchen didn’t open for lunch until 1 pm:(

I say my goodbyes to the staff and Abdou and learn quickly what Kath was referring to. The road, while picturesque, is full of deep potholes we swerve widely to avoid, playing an interesting dance with oncoming cars. It is clear why there is no roadkill here despite many wandering animals — dogs and cows and sheep and chickens — as it’s fairly difficult to get up much speed.

At one point, Hassan stops and rolls down his window. He talks to a man in the street and hands him some money.

“He fills in the roads with dirt, for free, just volunteer, so we try to help him buy what he needs,” he explains. It is one of those moments when I appreciate so much the connection between people here, how they help one another when the infrastructure is not necessarily being fixed by the powers that be.

I am also amazed by the public transportation, how men hang on to ladders of the vans, sit atop them. It is a reminder of how differently we deal with things here in the U.S., our rules and regulations that other countries do not have.

Another gentleman has driven with us, having visited his brother in the hospital in Ziguinchor, and he reaches out the window with money for a woman to bring bags of water to the car, the Senegalese version of a drive-thru.

As we approach Kafountine, I am aware that we are driving bumpily along something akin to the washes or arroyos that I grew up with in Tucson, Arizona, basically a dry river bed. Clearly the summer Monsoon season (what we also call our summer storms in Tucson) brings flooding here, and we bounce along around and through the deep grooves that the water carves into the earth. The dirt roads are narrow, and avoiding trees and fences is clearly something Hassan has mastered (a mastery Kath mentioned, likely to assuage any nervousness I might have when she mentioned the challenging roads.)

I am glad when we finally turn in to The Kora Workshop compound, and am thrilled to be greeted by Kath, and her partner Adam, who run the place. They have waited for us for lunch, cooked by Hassan’s wife, and their baby daughter joins as well in the open-air kitchen/dining area. I will be here for the next six days, and I feel a tingling of excitement at my great luck having discovered it on the Internet, googling “music lessons in Senegal.”

Cats meander playfully, and the setting is wild and spectacular. Kath Pickering and Adam Doughty, both from England, bought the property in 2007 “with the aim of bringing the kora to as many people as possible,” and have cultivated their large parcel of bush to host guests 7 months of the year to learn and play the beautiful koras that Adam makes and ships around the world. The kora, used extensively in West Africa, is a 21-string instrument often described as somewhere between a lute and a harp. I have seen it played a few times in New York by a man from Mali, Yakouba Sissoko, but was lured as much by the setting as my desire to learn to play. So here I am.

After lunch, Adam walks me down the long dirt path to my room. I have no idea what to expect. We pass through a gate and over to a thatched roof little house with a perfect tiled deck. He opens it to reveal a simple round room with a small shelf and hooks for my things, a bed with mosquito netting and side tables. There is no electricity and he tells me that I will be given a lamp.

He brings me over to the enclosed mosaic-tiled bathroom and reveals the compost toilet—a bucket with a toilet lid—where he informs me I can “cover what you do with this sawdust,” a material he points to in another bucket. I nod, smiling in part to cover up my surprise. I have not imagined fully what it would be like here, so surprise is a strange emotion. I stand taller in somewhat strangely false pride that I am excited about this revelation, at my hardiness where once I might have been dismayed or even disappointed.

There is yet another bucket, and Adam suggests I can put out in the hot sun during the day. “If you’d like a hot shower,” he says, as the handheld shower sprayer he points to and warns has low water pressure will only sprinkle out a bit of cold water.

There is toilet paper, I note, and soap. There is a towel on my bed. There is also a large ceramic vase with a lid that I am informed will be filled with water I can drink. Luxury.

Explaining the bathroom protocols, he suggests I might want to take a bucket into my room at night. And then, looking around my vast private garden he shrugs, “Really,” he says, in his lovely English way, “you can pee anywhere you’d like.”

I laugh at this, first lightly and then basically double over. I’m not sure Adam understands, and it’s hard to explain why I love this directive so much, why it is basically the best suggestion any lodging host has ever given to me.

I finally control myself and wipe my eyes. “I love that,” is all I can muster. “Thank you.”

With some hindsight I can see that this is the moment during the trip that I know I have come to the right place. When I am back home, hiking in the woods upstate, this is my favorite thing, to stop wherever I want, and pull down my pants, and pee. It is in those moments that I am free from the rules and restrictions that sometimes seem to choke every natural impulse out of me in the city, that force me almost constantly into the role of follower rather than allowing me to figure my own way. It might seem strange, but the lovely lilt of an Englishman who’d made his home in Africa, and welcomed me and others to come enjoy it, suggesting, “pee wherever you’d like” made me feel like maybe there was some hope for a better world. Weird, I know. But there are those moments when happiness overtakes you where you have to stop to try to understand why.

It has been a process in the days since I arrived, undoing all my cultural conditioning, trying to let go. I am not at all there yet, and as I ask Adam questions about the next few days, about the beach, and kayaking, and, and, and…he warns me that all that I want to do in my short stay will be hard.

But I am here five days, six…I protest. Mostly people stay weeks, even months I gather. They linger, it seems, and let go. I feel guilty somehow for my limited stay. I feel in his tone that I am rushing things, like an American, like a New Yorker, and I try to remember Alpha’s voice, and hands: tempo, tempo.

And then he leaves me there, and I crawl into the low-hanging hammock. I read a bit and take in the chorus around me, just listening to the thrum of birds. There must be hundreds of different kinds and as my ears begin to attune to it, it sounds like a crowded amphitheater, like a sporting event or concert in the distance. There is definitely a large gathering, but this is of birds, free singing birds, and the occasional moo of a cow. They are singing their own songs on repeat, paying no mind to one another seemingly. I hear some rustle in the leaves nearby and I turn only once to see the orange-billed birds nosing around in the earth.

And the intermittent drum beat is almost imperceptible, it is almost as if I am only imagining it, ba be dum dum, ba be dum dum…

And it makes sense to me suddenly, the music of this place, the derivation of it, the necessity of it. I hear it in the bird calls, the rhythms of the language, of the djembe, of the Gongoma. The patterns are the same, and they repeat, over and over again. It is a language for sure, the insistent whistling birds are the teachers. Over and over and over again.

Wolof makes sense. Jerejef, Jerejef, Jerejef. I hear it in the bird cries. Thank you. Thank you. Thank you.

I wake from my nap to wonder if what I hear in my dreams is real, the beat of a drum, the fast monotonous slaps that erase all coherent thought, that demand focus only on them.

It is a drum, and as I listen to it, I hear birds singing along and in opposition. There is a crazy cacophony to this African bush I have arrived in this afternoon. It is no wonder my hosts looked at me the way they did, and left me for a while in my own space, to get settled in, to lose the stench and strain of city life, even African city life.

There is a communal dinner, guests intermingled with people who work for Kath and Adam. It is a fascinating cast of characters and I am a bit overwhelmed though, frankly, excited to be able to have interesting conversation in English. It is an array of Europeans — from Brussels, the Netherlands, Switzerland, many from the U.K. I am the only American and I am sheepish a bit but no one seems to care all that much.

Kath takes my phone to charge it overnight via her own solar-power as I have no electricity in my little house. I go to bed early, walking with my little lamp down the long path, grateful that I have done a fair bit of camping alone. Hearing rustling I am reminded of Adam’s warnings about some venomous snakes that have been known to appear, or some cat-like creature he can’t conjure the name of that sometimes shows up. I hurry into my room and lock the door behind me, try to shut the wooden shutters on the windowless window frames, imagining the snake slithering through the bars…

I take down the mosquito netting even though I have not seen any mosquitos. I am slightly ill at ease in the middle of this wild land, but also excited to be here, and proud that I am working on my fear, which I know is driven mostly by my imagination. I know I will feel more comfortable the longer I am here. I tell myself, from experience, that I will adjust, and I settle into a happy sleep.

Feb. 26 - Kafountine

I wake this first night and have no idea what time it is. My computer still has a tiny bit of juice left, and I look to see it’s 1:47 a.m. I hear what sounds like a gunshot through the silence. And then another. I am somewhere so vastly different that I don’t at all know the meaning of this, whether to be scared or not, whether it is violence, or the sacrifice of a lamb. [I find out later it is part of a coming-of-age ritual for boys.]

What is lovely here is the mystery of my days, the not knowing at all what might arise, what is customary, what is possible.

I lie there and ponder how even the basics, like going to the bathroom, has been a strange sort of inexplicable puzzle. I got to laughing with the French dancer/choreographer whose family I took the boat ride with in the Casamance River about how no explanations are offered about how to use the facilities—the usual placement next to the toilet of a big bucket and a smaller one inside, the sink a bit too far from the toilet to really use effectively like a bidet, the lack of toilet paper.

On the little sandy beach of our hotel, as we laughed about our ignorance and confusion here, especially around how to handle getting one’s monthly menses, she somehow managed to turn the conversation into a sort of expressive dance, twisting and turning with her description of having her period in West Africa, and I was doubled over.

I think as I lie back that Senegal maybe isn’t a place for people who need to know exactly what to do, to be told, or to know already out of familiarity. If you don’t embrace the unknown, or want to learn how, traveling to West Africa is probably not for you.

I go back to sleep and am woken at the first light by a chorus of bird songs. I throw open the wooden blinds, and am newly amazed at this setting, already more comfortable with the compost toilet and ADORING the privacy of my area and an outdoor shower…what I’ve always wanted, to be freely naked in the out of doors, a hard thing to manage in Brooklyn:)

I head out of my little house to the dining area, around 8 as I recall someone saying was when breakfast is served. There are hot grains (not sure exactly what) and little buckets of peanut butter and nutella. There is cut up papaya, and bananas. There is coffee.

Josh, Adam’s son, had just wrapped up his annual two-week Kora workshop when I arrived, and some of the regulars, who have returned again and again to Kafountine to study and live, are still lingering about. George and Charlie and Jake are young Englishmen who are learning the kora, and Woolof. Jasper, also English, is a musician who grew up near Adam. Josh was his babysitter, and decades later, he finally came to visit West Africa and fell in love with the kora and other West African instruments and its people. He is making an album, and also a documentary about the beautiful fishing culture here (complete with traditional singing rituals during the catch), and the threat that Chinese trawlers present to it.

We are to meet in a little covered area to start kora lessons with Adam. Annemarieke, from the Netherlands, has already been here a couple days, and Stefano, an Italian/German who lives in Brussels, plays the kora at home. I am the most clueless. The instrument I am lent is beautiful, the back studs on it forming a beautiful heart.

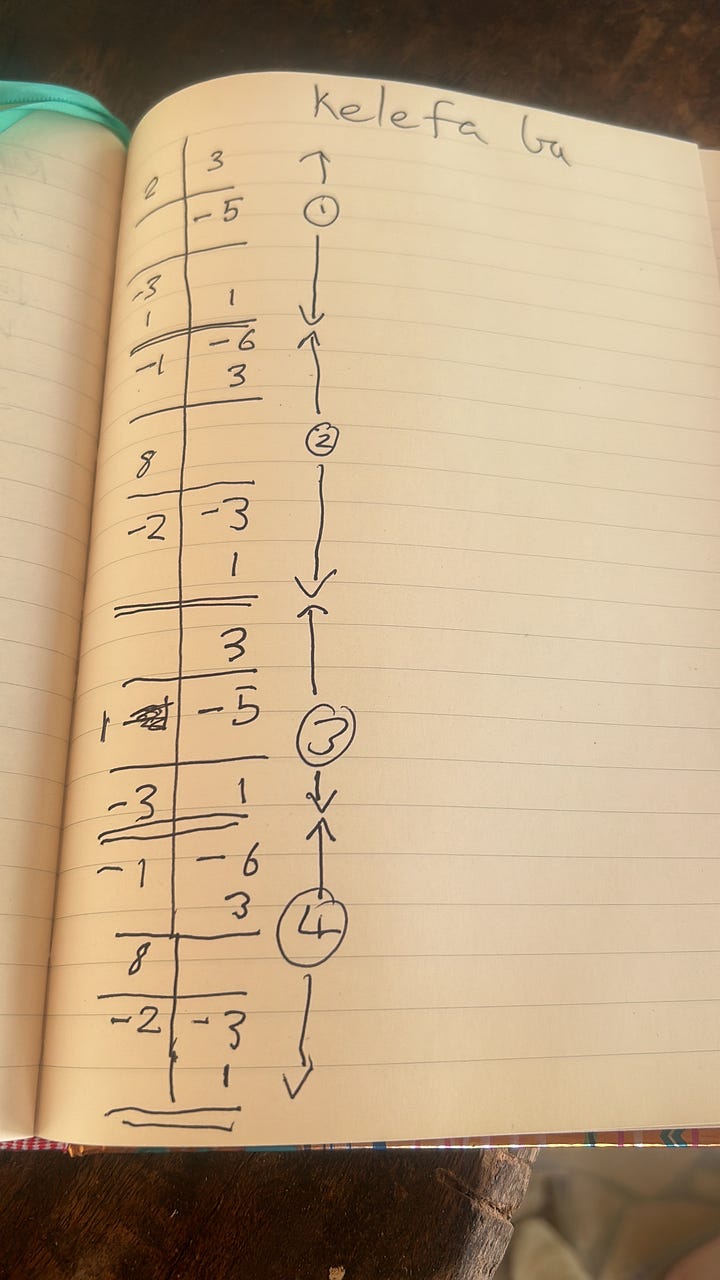

It is a slow start, and I write down the numbers—negative for the ones you play with your middle finger, counting from the top, and positive for the ones you play with your thumb, counting up from the bottom. Gulp. There is the left hand and right hand, and trying to play the traditional song, Kalifa Ba, proves a challenge. I am embarrassed at my lack of facility, and Adam suggests I break away to practice on my own. I have not come here to become a master kora player, but had hoped it would come easily to me to learn. Ha.

Unlike my own playing, the sounds emanating from others as I wander the property is ethereal. Combined with the lush overgrown vegetation, where even the sticks I pick up are curlicued and exquisite, I feel as if I’ve gone to heaven…Here is a little sampling of some of the jams that happened around and about during my stay!!

From left, Bienvenue singing, Charlie on kora, and Jake, on kora. I can’t help but hum along!!

Jasper, singing along with the kora.

Thanks for following along as I slowly eek out memories from my travels…I will soon get back to sharing some of my beautiful musical and cultural experiences back in New York.

After a teaching experience in a lower and middle school in Brooklyn upon my return, I have been developing ideas for creating a school exchange program to teach West African rhythms to children here in New York and in Senegal, and have them write letters to one another about the experience…reach out if you might be interested in supporting this effort in any way, especially if you are affiliated with a school that might be interested!!

Next up on the final days of my journey: a beautiful concert in Kafountine with headliner Seckou Keita, a beautiful kora player/drummer from Ziguinchor, and more music lessons with amazing local teachers.

Thanks again for reading! Subscribe, comment, share. Would LOVE your feedback!!

In peace + harmony.

Steph

Steph!! Your writing sings with such warmth and curiosity, it’s a gift to glimpse the world through your eyes. Jerejef for sharing your magic! 🙌🎶